SANETTE TANAKA

Many home buyers are victims of money illusion: They believe they are doing better if they sell their home for a higher dollar amount than they bought it, even if inflation eats the gains. Photo: Anna Parini.

Home sellers, be warned—that attractive house price might be nothing more than an illusion.

Many home buyers and sellers fall prey to the phenomenon of “money illusion,” says Lucy Ackert, professor of finance at Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, Ga., who studied money illusion in residential real estate.

Money illusion occurs when people think in terms of nominal values rather than real values—meaning, they consider the face value of money instead of its actual purchasing power.

“Homeowners don’t think in real terms. They think in nominal terms. Many people would prefer a situation where they have a real loss, than a real gain and nominal loss,” Prof. Ackert says.

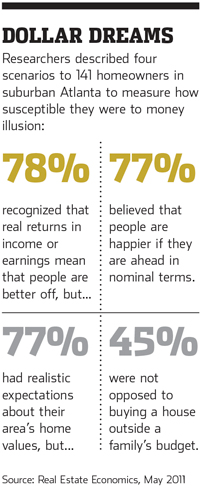

Prof. Ackert and co-authors Bryan Church and Narayanan Jayaraman of the Scheller College of Business at Georgia Tech presented 141 homeowners in suburban Atlanta with four scenarios in October 2005, near the height of the housing bubble. The researchers then determined respondents’ propensity to fall prey to money illusion. Their study, “Is There a Link Between Money Illusion and Homeowners’ Expectations of Housing Prices?” was published in Real Estate Economics in May 2011.

Prof. Ackert noted that respondents weren’t disillusioned about the price of their house—77% had realistic expectations about their area’s home values. Most respondents also understood that a person is better off financially if real returns are higher.

But, in keeping with money illusion, people base happiness around nominal values—77% of respondents believed that a person is happier if they are better off in nominal terms, even if real returns decreased.

Why does nominal win out?

Simply put, it’s easier to think that way, says Alan Cooke, a marketing professor at the University of Florida, who studies consumer decision-making.

“People tend to expend as little mental effort as necessary to make a particular decision. So, if you have the opportunity to consider things in nominal terms rather than real terms, that’s what people will focus on first,” says Prof. Cooke, adding that people will put more effort into making decisions that they see as more important.

Sarah Lanigan, 35 years old and a mother of two, recently moved from Davis, Calif., to Portland, Ore. Ms. Lanigan says she tends to think of house prices in face-value terms while her husband, Ryan, who once worked as a mortgage banker, looks at them in real terms. “I’m not oblivious to it, but it’s not at the forefront of my mind,” she says.

“Things like stickiness in prices, nominal versus real—that’s not the average conversation you have with a client who’s about to buy a piece of real estate,” says Maureen Mestas, associate broker with Sotheby’s International Realty in Santa Fe, N.M.

A housing bubble can be generated when people believe prices in the future will be higher, and are thus not worried about overpaying today. Prof. Ackert says money illusion alone won’t cause a housing bubble, but when coupled with tight supply, “that’s when you really run into trouble. It’s a perfect storm,” she says.

Write to Sanette Tanaka at sanette.tanaka@wsj.com

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304756104579453383125973334?mod=WSJ_RealEstate_RIGHTTopCarousel&mg=reno64-wsj&url=http%3A%2F%2Fonline.wsj.com%2Farticle%2FSB10001424052702304756104579453383125973334.html%3Fmod%3DWSJ_RealEstate_RIGH