Economists Debate Whether School Loans Are Undermining the Housing Recovery

Rachael Heffner, like many Americans, has long had a dream of owning her own home. But the college graduate also has a much newer problem blocking her way: a $691 monthly payment to service her nearly $60,000 in student loans.

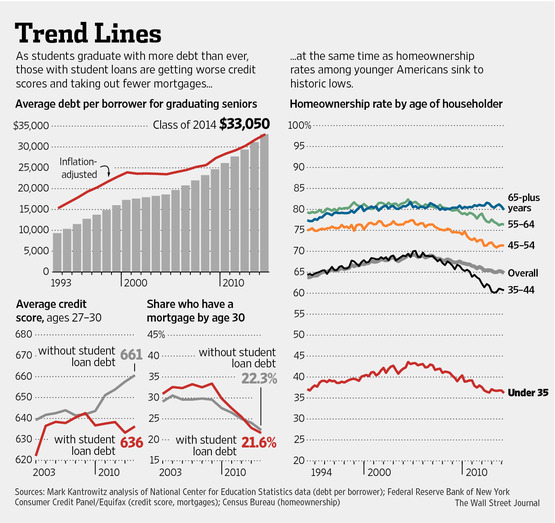

Homeownership among Americans under age 35 hit the lowest level on record earlier this year, just as indebtedness among college grads notched a new high. That has stirred debate among economists and policy makers over whether the two forces are related: that high student debt is driving the fall in home buying among the young and harming the U.S. economy.

That, along with a jump in borrowers, has pushed overall student debt to $1.1 trillion, almost double the load in 2007, much of it at relatively high interest rates. The homeownership rate among those under 35, meanwhile, has fallen to 36.2%, from a high in 2004 of 43.6%.

Former White House adviser Lawrence Summers is among the economists arguing that student debt is undermining the housing market and damping the U.S. economic recovery. “Overly indebted households are not in a position to spend and move forward,” he said recently.

Others say the two aren’t necessarily related, noting that years of academic research have yet to draw a firm line between rising student debt and the decline in home buying among young Americans.

“There’s no evidence to say that this decline isn’t entirely due to the economic downturn and lenders adopting more stringent underwriting criteria for mortgages,” said Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of education website Edvisors.com, who has studied the economic effects of student debt.

Economists say many factors could be driving the drop in homeownership among younger people. Home prices have risen quickly as Americans’ wages have stagnated. Lenders are still imposing tight standards, directing loans to the safest borrowers. And Americans are waiting until later in life to marry and have children, which reduces the urgency for home buying.

Most economists agree that producing more college graduates improves the skills of the workforce and boosts the economy’s growth prospects. Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen, for her part, has said she sees student loans as a key tool allowing families to afford a college education and improve lifetime earnings, even as she has expressed alarm about the debt being a heavy burden on some families.

The effects of student debt differ from household to household, boosting the prospects of some while effectively trapping others. Ms. Heffner, 29 years old, is among the trapped. She and her boyfriend rent her parents’ basement in Millersburg, Mo. She wants to buy her own place, but payments on her student-loan debt amassed getting a bachelor’s degree in graphic design gobble much of her $28,000-a-year salary as a sales assistant at a local television station. Her dream, she says, is “to own my own house, to be able to paint walls, hang things up on the walls.”

For others, like Jena Bright and her husband, Thomas, student debt has led to degrees and decent-paying jobs. Ms. Bright, 24, used $27,000 in student loans to become the first in her family to graduate from college, in 2011. She immediately landed a job at a Richmond, Va., design firm and earns near the area’s median salary of $46,500. She and her husband, Thomas—also an indebted college grad who earns a similar salary—are under contract to purchase a $200,000 home. “It’s worked out for me,” Ms. Bright says.

Anthony Hsieh, chief executive of loanDepot.com, a California-based mortgage lender, cites as one complication new federal regulations that force lenders to be more stringent in assessing a borrower’s ability to repay. Lenders now weigh student debt more prominently in determining creditworthiness than they did before the crisis, he said.

Research by the New York Federal Reserve Bank shows that before the recession, Americans at age 30 with student debt were more likely to hold a mortgage than those without. But people without student debt are now more likely to hold mortgages.

Americans with student debt also have seen their credit scores plunge as delinquencies rise, with the average score in the low 600s. Average credit scores on home-purchase loans stand in the mid-700s.

Tiffany Reed, a Rock Springs, Wyo., veterinarian, says the $65,000 she earns each year gives her the means to pay down a mortgage, but tough lending standards have stood in the way. Three years ago, a lender rejected her because of her nearly $450,000 in student debt, including interest, mostly accrued at veterinary school. So Ms. Reed, 33, bought a mobile home from an acquaintance, paying him monthly.

“I was so surprised when I was turned down. I’m a doctor. I have a good-paying job,” Ms. Reed said. She plans to make payments for an additional 25 years under the government’s income-based repayment program, then hopes to have the remainder forgiven.

Write to Josh Mitchell at joshua.mitchell@wsj.com

http://online.wsj.com/articles/student-debt-takes-a-toll-on-some-home-buyers-1403305623?mod=WSJ_Your_Money_3up