Some decline in the labor force was expected as the massive baby-boom generation born after World War II began turning 60 and retiring by the millions, in the mid-2000s. Few retirees return to jobs. Around 18% of those over age 65 are in the workforce.

The decline in boomer participation isn’t the sole reason behind the decline. Another big explanation could be that people who drop out amid a bad economy can’t easily be enticed back. Economists call this labor-market scarring. People find other ways to get through life, even precariously, by relying on friends and family, going on disability or retiring early.

“You can leave for economic reasons, but it doesn’t mean you’re going to come back for economic reasons,” Mr. Feroli said.

Determining the cause and finding solutions for depressed participation has important implications. The size of the workforce is a key determinant of how fast the economy can grow. A smaller workforce presents a drag to growth. With fewer workers paying taxes, the government’s fiscal picture is more challenging. In the late 1990s, when the U.S. last ran budget surpluses, the participation rate was nearly five percentage points higher than today.

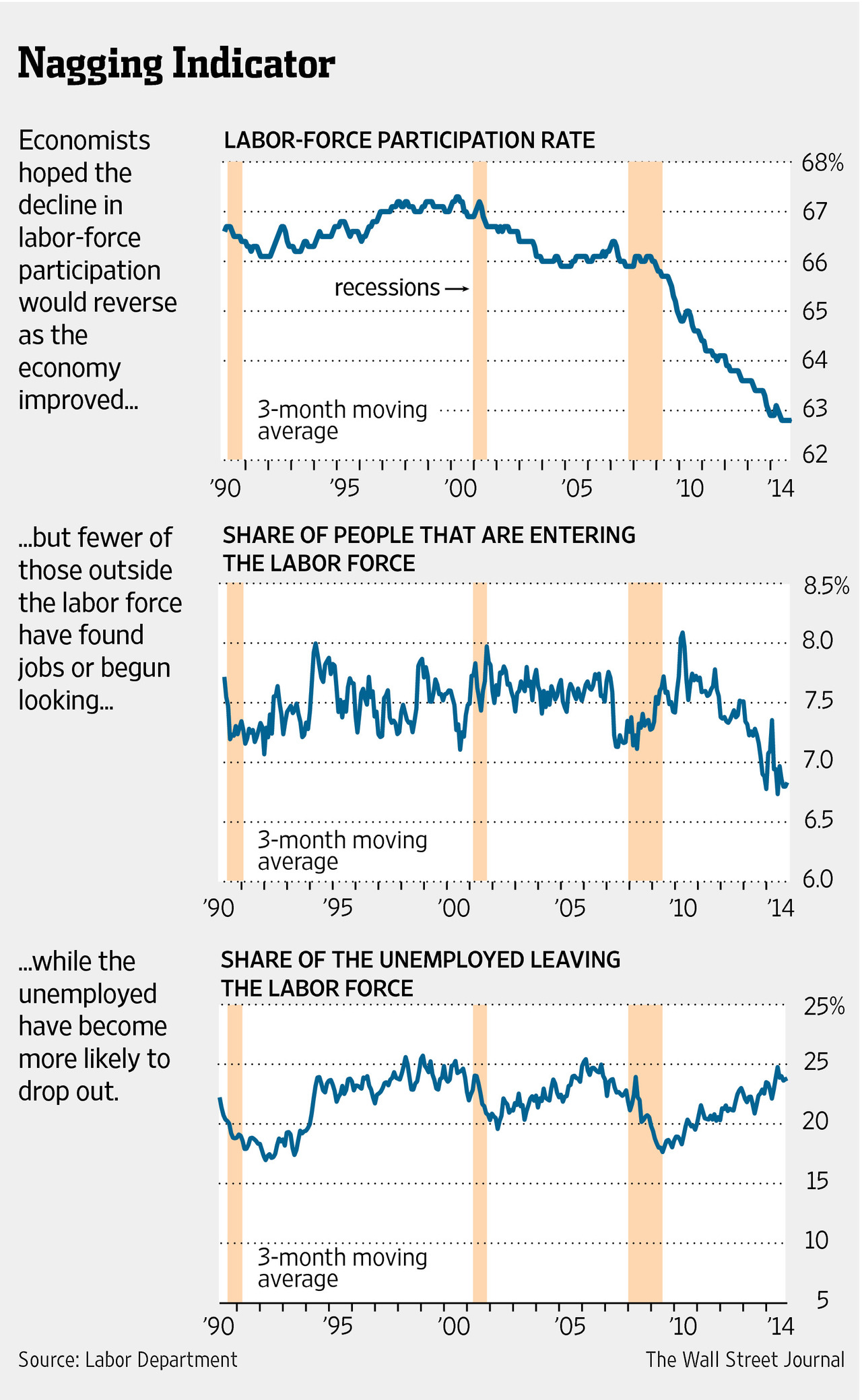

In recent years, Fed officials had cited the declining labor force as evidence of economic slack. The traditional unemployment rate counts only those actively looking for work; those who stop looking entirely are counted as labor-force dropouts. The Fed pressed on with easy-money stimulus efforts, citing the belief that the jobless rate, while declining, understated the true extent of economic weakness.

Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, for example, espoused the central bank’s consensus view. In March 2013, when the unemployment rate was 7.7%, Mr. Bernanke said discouraged workers would return. “As the economy strengthens, the labor market strengthens,” he said.

The unemployment rate since then has fallen by nearly two percentage points as the economy added 4.4 million jobs. Consumer sentiment has gradually climbed to the highest level in nearly eight years. The flow into the labor force, however, has declined.

The Fed’s explanation that dropouts will return is “losing a little bit of traction because participation is just not going up,” said Joseph LaVorgna, chief U.S. economist for Deutsche Bank.